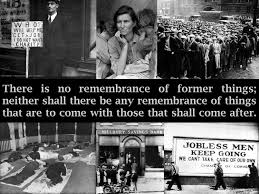

When the stock market crashed in October 1929, plunging the United States into the Great Depression, the country entered one of its darkest economic chapters. Over the next decade, unemployment soared to over 25%, banks failed, families lost their homes and farms, and hope seemed in short supply. But amid the despair, many Americans found strength not only in government programs and personal perseverance—but also in faith.

Religion during the Great Depression played a crucial role in sustaining morale, inspiring resilience, and mobilizing compassion. For millions of people facing hunger, homelessness, and uncertainty, churches, synagogues, and religious charities provided both spiritual comfort and tangible support.

In rural communities, particularly in the South and Midwest, Christian churches were lifelines. Ministers preached about God’s faithfulness, even in suffering, drawing from familiar biblical stories—like Job’s endurance, the Israelites’ slavery in Egypt, or the widow of Zarephath who was sustained during famine. Many pastors urged their congregations to hold fast to their faith and to believe that God was working even in the silence.

At the same time, urban congregations faced overwhelming need. In cities like Chicago, New York, and Detroit, churches opened their doors to the poor and the jobless. Some transformed sanctuaries into soup kitchens or shelters. Catholic parishes distributed food and clothing. Jewish charities and Salvation Army outposts operated on shoestring budgets to meet growing demands. These religious institutions often filled the gaps where government aid was lacking or slow to arrive.

One of the most visible religious figures of the era was Reverend Charles Coughlin, a Catholic priest whose weekly radio broadcasts reached millions. Initially supportive of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, Coughlin eventually became a controversial critic. While his later years were marred by divisive rhetoric, his early broadcasts reflected the spiritual yearning of a nation looking for answers, blending biblical themes with economic commentary.

On the other side of the spectrum, African American churches served as both spiritual and social centers for Black communities, who were among the hardest hit by the Depression. Faith leaders preached messages of endurance, justice, and God’s concern for the oppressed. Gospel music—rich with emotion and rooted in the Black experience—rose in popularity during this time. Songs like “Precious Lord, Take My Hand” became anthems of spiritual survival.

The federal government also recognized the importance of faith during this period. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, though not overtly religious in style, often spoke of divine guidance in his Fireside Chats and public addresses. In his First Inaugural Address, he invoked God’s blessing on the nation’s efforts to recover:

“In this dedication of a nation, we humbly ask the blessing of God. May He protect each and every one of us.”

FDR also supported the Federal Council of Churches and other faith-based organizations working to alleviate suffering. The government and faith communities did not always operate in harmony, but their missions often overlapped—serving the downtrodden and restoring dignity to the forgotten.

The Great Depression forced Americans to confront not only financial ruin but spiritual questions: Why had this happened? Was it judgment? A test of faith? A call to national repentance? In response, many found a deeper dependence on God, a renewed emphasis on community, and a commitment to caring for one another.

In the end, while the Depression tested the nation’s economic and political foundations, it also revealed the quiet strength of American faith. It was in the bread lines and the revival tents, in whispered prayers and shouted hymns, that millions found the courage to keep going—and the belief that better days would come.